Dr. Sharon Tao

What would it take for you to give up your successful career and life of comfort to trade it in for unpaid work in a shack, with no running water, and intermittent electricity?

At the top of her game, Sharon Tao gave up a comfortable life in Amsterdam and traded it in for an orphanage in Tanzania. You can read more about this in Part I and Part II of this story series.

And what would you do, if you were witness to children receiving violent corporal punishment every day? Would you intervene? Or would you do nothing?

Read on to find out why Sharon Tao did nothing…initially. Then brilliantly used her powers to learn more and develop alternative ways to discipline 100 kids in a classroom.

In my eyes, Sharon is one of the world’s unsung heroines. She sacrificed her life to use her powers for good. In Part III of this interview I was curious to know if Sharon had a hero of her own in life, someone that she looked up to for inspiration.

I wanted to find out what her hardest challenges were and what she treasures about the journey that led her to a PhD and a Leadership role with the Girls Education Challenge.

ST: Well I thought of Winnie, in that story. Certainly someone….

Winnie, her puppy, jumps up onto a Sofa…

Winnie! Down! Not that Winnie – (Laughs out loud).

But yeah, that’s a good example of someone who was so inspiring that she changed the course of my life! And I agree, the sort of idea of the everyday hero, someone who doesn’t necessarily get the recognition of celebrity or money or whatever, um, but deserves recognition.

Winnie comes over for a scrunch and I pour a freshly brewed pot of green tea.

ST: I thought about what was the toughest experience whilst I was in Tanzania and Rwanda. And this one came fairly rapidly.

I am going to say this not as a form of judgement – but the amount and degree of corporal punishment that was there. I mean corporal punishment is a classroom management tool. Because teachers don’t have any training in any other classroom management tool. If you have one hundred children in a class, it’s a very efficient and effective tool.

So certainly the, toughest experience was the first time I volunteered at my school… The school I was at in Tanzania, I volunteered three times. The first time was a short stint, the second time a longer stint and the third time I went back for my Doctoral research. And, all 3 times…

SBN: For example ….

ST: There’s lots of different types of corporal punishment, and reasons for it. And degrees of it.

I mentioned the classroom management tool. And I remember a class of a hundred kids and watching the teacher take a stick – just a branch from a tree, not a big one, just a little one – and they would just bang it on the desk to get the children’s attention.

So that’s scary, and it gets people’s attention very quickly. Another classroom management is they would just kind of walk around with it.

Like a pointer – but generally a weapon, you know, that can be easily used.

Other times, other forms of corporal punishment, yes, if you do something naughty it’s a consequence. Or it’s more systematic. If they do assembly in the mornings, it’s almost kind of like an inspection. So if your late, if your collar’s dirty, if you haven’t paid your school fees on time they kind of put you in a queue and literally (smacks palm of her hand against the back of her other hand repeatedly)…. You know one after the other.

That’s the kind of systematic – don’t do that again, type thing. Then there’s the really bad; you’ve been caught stealing.

Parents bring their kids to school… to legitimize the punishment. I’ve no doubt that happens at home too. I remember one boy being brought by his parents to have the teacher also cane him because they caught him stealing.

It is much more violent and a consequence for being a thief. It’s proportionate; the punishments to the offences. But I think for me it was really difficult to watch. Because obviously I come from a completely different background and education.

I’ve never experienced that, nor seen it. That’s not to say that it hasn’t happened in our context, I mean the UK only just banned it in the 70s or early 80’s. That’s what I mean about not trying to cast judgement.

But my personal experience I had never seen it, felt it, experienced it. And certainly not to the degree of real violence. So it was just really difficult to watch.

What was also worse, was the tension of not doing something or trying to work out if I should do something. I remember, in those first three visits to that school, the first time I was just so overwhelmed. I didn’t know what to do. So I didn’t do anything.

The second time I went back, I again was overwhelmed and horrified. I had heard about an Australian volunteer, who was there a few months before me. She immediately went to the Head Teacher, after seeing a teacher cane a child, and said, “if you don’t do something about this I am going to the District Education Officer….”

She was a volunteer who was there for about 3 – 6 months. Who are you to tell me, volunteer teacher who’s been here for three months, how to run my school and how to manage my teachers!

And so he (the Head Teacher) didn’t respond. She went to the District Education Officer, and …

If her ultimate aim was to get teachers to stop caning the children, that was not the way to do it.

As a white western woman with very different cultural belief system, expectations and understanding of teachers…. She tried to use that power to get something done in Tanzania. And it backfired.

It made the teachers resent her. It made the Head Teacher resent her. No one was going to listen to her after that. And certainly no one was going to stop caning.

When I heard that, I remember thinking… ok my instinct of being paralysed and not sure how I wanted to respond. Knowing I wanted to, but not entirely sure why, and now I could see why…

That was a pretty good explanation of why using your power and position from a western ex-colonial (well it’s all conflated anyway) country is not necessarily helpful either.

The third time I went back doing my Doctoral research, I remember thinking, ok – I’m not going to try to wield my power because it’s not going to work. And it’s probably going to backfire and the teachers won’t listen to me.

However, what I can do is try to understand why teachers are doing this and understand. I was doing research on teachers and talking to them so I just added that as a question during the interviews. To ask. And it was nice, because they trusted me. My third time back at their school they knew me. So they could be quite candid and say, “I feel forced to, I don’t really like it…but I don’t know what else to do.”

Or, “I’m angry and I can’t help it.” Often times what it came down to was not having any alternative way to respond. Whether it was out of anger or frustration, you know, managing the class they didn’t have any alternatives. That was the only course of action. A lot of teachers were beaten as children and they did not enjoy it.

SNB: Learned behaviour…

ST: It is. And the fact they don’t have any alternatives.

So I made that part of my Doctoral research. To provide that complex explanation and nuance as to why teachers engage in corporal punishment.

And if you can understand that better, then any kind of intervention to reduce it gets at the nub of why they’re doing it. Rather than just coming in from a positon of power and saying don’t do this – child rights – blah blah blah.

Then they look at you. You’re an outsider… you don’t have to live through this every day – for fifty years. And who are you to tell me what to do?

So that was really tough, uncomfortable, horrible … I saw some hor-r-ible, horrible things.

I remember at one point having my mouth agape and one of the teachers just laughed at me…well not laughed, but said,

“Sharon, this is Africa – just deal with it”.

My heart sinks to hear this… Sharon’s voice is steady, light and a matter of fact. Ever the professional. But I can see her eyes soften when she talks about these memories.

SBN: Did it happen on a daily basis?

ST: Oh yeah. What was interesting in my research I analysed. I was working in three different schools, with 3 different degrees of corporal punishment.

One school was really bad because the Head Teacher endorsed it, he expected it from his teachers, he did it a lot, that was the go to tool.

The second school had a female Head Teacher. And she had a Deputy of Discipline. She didn’t condone it necessarily; she didn’t do it herself. But if a child was in the office, you could hear him or her crying.

And the third school, was a teacher who –

I mean the law in Tanzania is it’s against the law. Corporal punishment is not allowed.

It’s not enforced and that’s the thing… But she was enforcing it. Her school actually had a lot of western volunteers and it was attached to an NGO. She had kind of taken on board it’s the law – I don’t want to see any teacher caning children. And she was very explicit.

So what happens? The teachers hide it from her. So it happens less because she’s on the lookout. But teachers were still hiding it from her. So it happens in different degrees, from all the time, every day in the open, in the playground this is an example, to kind of hidden.

SNB: How did you cope with this? What got you through, every day seeing this?

ST: It was difficult in the moment watching it, certainly.

But I always said to myself – I am here to do my Doctoral research, to understand why teachers do what they do, including caning children. Then what I can be using this experience for is to try turn this research into something that can be a thoughtful, nuanced, sensitive intervention. To help teachers stop doing that. So the training subsequent in my work now that I’ve done to help teachers is to first prime them.

‘Go back to when you were a child. Do you remember being caned? How did that make you feel?’

‘Oh that was hideous, that was horrible…’

‘Ok, so today’s training is about corporal punishment.’

So using that research, those stories and that understanding of why teachers are doing it. That desperate feeling of I have no other choice… and then coming up with new choices.

What was really helpful was the Christian Brothers, who I had volunteered with, they obviously understood the context but definitely didn’t engage in the caning.

They had some great classroom management techniques to settle a class. Or to deal with discipline. So that was the other trick. Because in my research I was also teaching participant observation. I had classes of a hundred.

So then we’d turn it into a game.

If you want the class to settle, you know, three teams of 30, they’re set up in rows. Set the behaviours that you want. And if there’s an infringement you take a point off. And they start to self-regulate.

It’s a game, they want to keep the points. I would do that in my class of a hundred. And then the other Tanzanian teachers would see me doing that. And then they listened to me.

Ok you’re an outsider and you’re doing what we’re doing…because that’s another thing that really pisses them off… you’re an outsider who works with 20 kids in a classroom. Who are you to tell me what to do – you have no idea what this is like.

So if I can manage, a class of a hundred without caning and show them…I proved to the other teachers that I am worthy of listening to.

SNB: It was amazing you were able to hold onto the big picture whilst you were in that moment of research.

ST: Did I know it at the time? I think it was more intuitive. And hoping that this would lead to something.

I wouldn’t say that I knew exactly – that was my hope.

SNB: On the flip side of that. What was the most rewarding experience you had volunteering in Tanzania?

ST: The first image that came to my mind, was: sun setting, walking with the kids from the orphanage. We didn’t have a well or a tap or any running water. So we had to walk to the river, which was probably about a kilometre or two away, to collect water.

Kids, buckets on heads.

I was dreadful, I kind of put it in bottles!

But I would go with them to help them collect water, and this was the first time I went to volunteer. I was just processing all the culture shock and seeing the reality of what the kids live through and all the rest of it. These kids had so much joy and happiness. And they happened to be teaching me how to count in Swahili. They would say, ‘no that’s wrong do it again’ – that was how they were taught… and it would crack them up!

It was more of a feeling, you know, it was seeing such joy in its purest form. Despite the fact that they were kids in an orphanage, walking two kilometres to collect water through a municipal dump (tip)!

It was just one of those things whereby it was the irony of what could feel so stark and depressing at that moment, was lovely. It just reminds you of the resilience of these kids. And human interaction is lovely and amazing despite the context. There were plenty of amazing experiences of things that made me happy but that was the first thing that came to mind.

SNB: Seeing their happiness in everyday existence…

ST: Yes. Even though they had experienced a lot of sadness as well. And there were some screwed up kids, certainly. But in that moment, they were laughing at me trying to learn Swahili…. (Laughs out loud).

SNB: What are some of the biggest roadblocks that you’re experiencing at the moment for implementing the programs.

ST: (Sighs) … I was going to say budget cuts because that’s what’s happening right now! Actually no, that’s quite superficial.

What’s actually more of a barrier is the social norms and the structures around these social norms that are present in some of the countries that we work in. You know, the same stuff happens here, don’t get me wrong, so I’m not trying to cast judgement.

But we’re talking about norms of how we teach, corporal punishment, gender norms, they’re very deeply embedded and reinforced in the structures of the education system.

To shift them is very difficult. To shift the way teachers, teach is difficult and I don’t know if I see enough programs doing it in a thoughtful way. Often we see a lot of teacher training programs that aren’t sustained – I’m cynical – because they are designed by foreigners and westerners who kind of assume the reason teachers are teaching the way that they are is because they don’t know any better or they’re lazy or whatever.

So they come in and say – this is the way that you should teach – and it’s not really picked up. Well not by everyone.

The norms around gender, violence. Well gender with regards to early marriage, FGM (female genital mutilation) a lot of the reasons that keep girls out of school.

Those are really difficult things to shift especially as an outsider. And norms around violence. Both domestic violence in the house and violence in the school. Again, there are ways but I don’t know if the training I did on classroom management strategies worked. I didn’t end up doing research on the teachers afterwards. I wish I did, but I don’t know if they worked or not… so yeah…

SBN:… And what does your end goal look like?

ST: One of the theories that I learned in my Master’s degree. I remember being completely blown away when I learned about it. It’s a theory about development.

Historically, development was always about how much money was in your pocket. Right. It’s living under a dollar a day, that whole discourse. And this gentleman named, Amartya Sen, who was an economist, but a philosopher as well, developed this theory called the Capability Approach.

Basically what he posited is that development is not necessarily what you have in your pocket, money is important.

But that’s not the end of development.

The end of development is whether a person has the opportunity… a real meaningful opportunity to be and do what she/ he values. So if she values not being hit by her husband and she has the opportunity to not be hit by her husband – that’s development.

She could be the richest women in the world.

But if she doesn’t have that opportunity then it’s not development.

She doesn’t have a full, free meaningful life.

If a person values being able to walk down the street, even anonymously to get a carton of milk, something I couldn’t do in some of the countries that I lived abroad in. I wouldn’t say that meant I had a horrible life. I can survive without being able to walk down the street anonymously without people staring at me and you know, all the rest of it.

But it means my wellbeing is constrained. Slightly. But it is.

So what the Capability Approach posits, is to have a really meaningful wellbeing, is what the end of development is.

And that wellbeing is having the opportunity to be and do what you value. And of course money is important.

If I value being educated or doing my PhD or whatever, money will facilitate that.

If I value living in a house that doesn’t have a leaky roof and feeling safe. Yes. Money will facilitate that or lack of money constrains that. Lots of things constrain it, but lack of money can as well.

But the end goal is not the money. The end goal is having the opportunity to be safe. So for me that’s the end goal of development in general. Whether it’s in Denmark. Whether it’s in Tanzania…

If you don’t have meaningful opportunities to be and do what you value, then your wellbeing is constrained.

And so the context of the GEC that I work on. We can’t cover all the opportunities that a girl might want but we can focus on the educational bit. And if she values being educated and being able to read, then our program needs to do everything that it can to provide her the opportunity to do that. To reach her fullest potential and look at all the constraints on that.

If she values being able to read or to go to school… What are the constraints? Are they marriage, having to do all the cooking and cleaning…being tired all the time…not having time to study…not having a space to study… having no electricity.

You know there are a lot of things that can constrain her opportunity to do that. So for me, and I am not saying all of our projects are set up that way, but that’s my end goal. And that’s what I think should guide how a lot of projects are set up.

SNB: Amazing…

ST: (Laughs) And that’s what I loved about studying because when I read that, I was like, “Yes!”

SNB: Wow, fantastic… and is there a timeline for you? Do you plan to go back to some of these countries to see how things have progressed?

ST: This is the last five years of this program. So I’ve only come in the last 5 years, but it’s been going on since 2013. I’m sure if there was a reason for me to travel and support the projects then yeah sure. The interesting thing about COVID is that’s it’s made international travel not possible!

(Winnie jumps into Sharon’s lap. Sharon calls it her meerkat pose.)

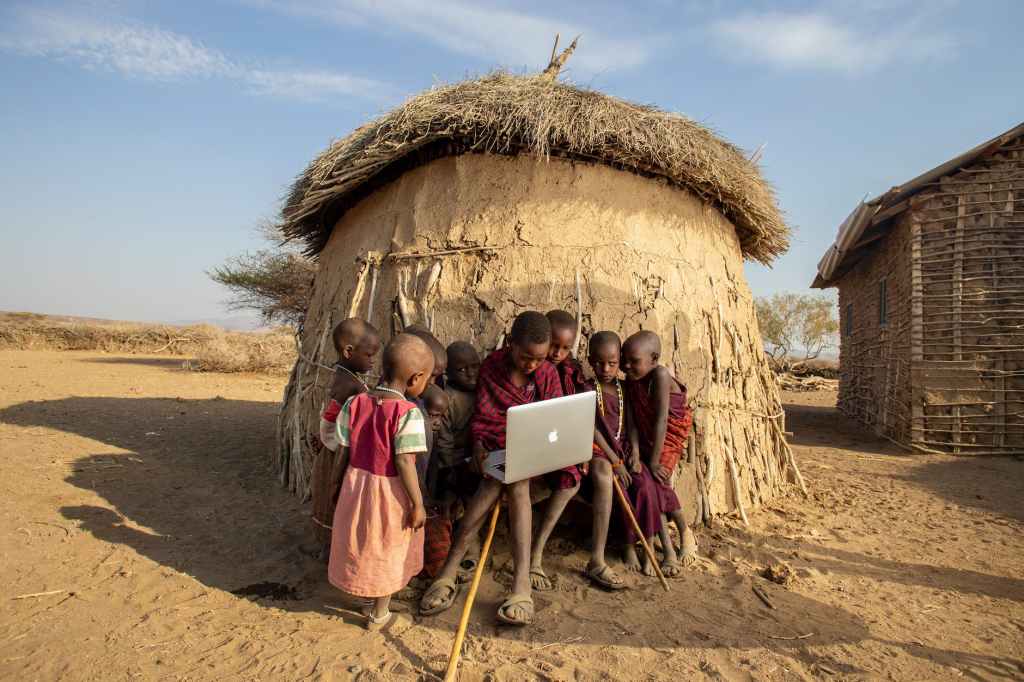

Not all projects are good. When you have 41 projects there’s always a spectrum. Some are doing fabulous things and some are struggling, certainly, for different reasons. But you’re right, even yesterday we had a closing event for a project in Kenya. And we did a video about a girl who benefited from the project. They had an interview with her father who was from the Maasai tribe. I taught in a Maasai school. Very traditional, very patriarchal, girls married off by 13. Girls very rarely, well maybe more so now, but girls weren’t meant to be educated.

So when I saw this interview where this dad, in full Maasai regalia, was talking about how proud he was. His daughter finished school because of this program. That to me makes it real and meaningful.

And of course we get caught up in trying to meet targets and 1.3 million girls and all of this kind of stuff. But often times it’s those individual stories that are very, very powerful.

And it makes you kind of feel better, that ok well as least we have positively affected one girl’s life. I know that’s not very – value for money but it’s nice to know and the hope is that there’s many of those girls who have benefited.

SNB: Great… let’s take a moment.

Last question as I know you’re pressed for time… What would be your advice to someone who obviously cares but not necessarily knowledgeable about how they can help… what would you say to them?

ST: Focus.

Because you’re right it is a vast sector. Social development, social justice, responsibility all of this sector is vast. And you could get very overwhelmed very quickly.

So I say this to anyone thinking of going into development, because they want to help people, they want to reduce poverty, but they don’t know how to help exactly.

I mean there’s so many aspects to it. I always kind of say, focus on the area that is meaningful to you. That you have experience in, and that you can contribute to.

So that’s how education landed for me, because I ended up, accidently, as an English teacher in a primary school. And that was my experience and that’s what prompted my focus on education.

I have health colleagues, you know, who kind of fell into it after being doctors and they’ve had their journey. I mean there’s so many different aspects to development, there’s governance, there’s faecal sludge management – I have a friend who deals with putting in toilets, which is really important! Hugely important to people’s health and sanitation… I don’t know how he got into that… I think he was an engineer actually.

But there’s so many different aspects to somebodies wellbeing. And what I think is important for you is to find out, what is meaningful to you. Where have you interfaced with this before. For example, I have another friend who focuses purely on violence against women. Because it’s meaningful for her.

When you can focus and be more specialised you can contribute more and be part of the dialogue with those people and organisations and that sort of thing.

SNB: Thank you so much for taking time out of your busy day and having this conversation with me over lunch. And thank you for brining Winnie for my dose of dog therapy. I still have so many questions! But perhaps we can discuss more over a drink next time!

ST: Thank you! It was my pleasure.

Scene by Nina’s stories are here to share, grow and celebrate. In Story No. 1 we celebrate the inspiration, hard work and insight of Sharon Tao’s journey. I really had no idea just how deeply moving Sharon’s story would be. Or the profound importance of Girls Education Challenge and how it’s impacting millions of girls’ lives.

Sharon’s story inspired me to dig deeper into my own social conscious. To consider my own constraints and how I can use my power for good. I have learnt so much from this experience alone. And I am so pleased to be able to share it here. I hope it will inspire you too.

If you are interested to learn more about the GEC, please visit the following links to their website, blog page and YouTube videos.:

https://girlseducationchallenge.org

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCmjvZBKujCeaPUcHrj5lRtw

https://girlseducationchallenge.org/blogs